You might look like you’re the picture of the health but do your insides tell the same story? HFG editor-at-large Niki Bezzant explains the signs to look out for.

We’ve all got that skinny friend who seems to be able to eat anything and not gain a gram. They probably don’t do any exercise, either. It can be frustrating – and seem highly unfair – to those of us who struggle with weight control, but still eat well and exercise regularly.

But it may be interesting to know that your thin friend may not, in fact, be as healthy as they appear on the outside. It’s possible to appear slim but, in fact, harbour unhealthily high levels of body fat on the inside. These are ‘skinny fat’ people; also known as TOFI (thin on the outside, fat on the inside). Scientists give this a slightly more technical term: normal weight obesity. And evidence is growing that this may be just as harmful to health as being obese.

What is normal weight obesity?

People with normal weight obesity have a body mass index (BMI) that falls within what’s defined as the ‘healthy’ range. But they also have a high body fat percentage. Research has found these people have a significantly higher risk of developing conditions such as metabolic syndrome, high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes and heart disease than those with a ‘healthy’ BMI without central obesity.

You may also hear the term ‘central obesity’ related to this. That’s when an excess of body fat is accumulated in the abdominal area. Of particular concern is visceral fat around the internal organs because this fat is metabolically active, producing compounds that trigger inflammation and releasing fatty acids into the bloodstream. That’s different to subcutaneous fat – the fat you can jiggle – that tends to accumulate around hips and thighs, which we might not like but is more benign, health-wise.

Normal weight obesity is more common than we might think. It seems to be more prevalent in men, with estimates in some populations as high as 30 per cent of men. Globally, the estimate is around 20 per cent of people. Local research on women’s body composition suggests between 20-28 per cent of Pakeha women in New Zealand may have this profile – defined as a ‘healthy’ BMI (25 or below) but high body fat percentage (above 30 per cent).

And it would appear to be growing. Australian research published in 2017 found waist circumference for individuals of the same body weight, height and age increased by 6.7cm among women and 2.8cm among men between 1989 and 2012.

The study estimated that one in five women and one in 10 men were obese according to waist circumference, even though they would not be detected as obese by BMI.

Many experts now suggest the definition of ‘obesity’ needs an update, to account not only for weight, but also adiposity – body fat.

Why is it so bad?

Experts now know that people who have an obese waist circumference (greater than 88cm for women or greater than 102cm for men) but who don’t have a BMI that would put them in the obese category (30 or higher) still have an increased or higher risk of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure and early death than those defined as obese by BMI.

That’s likely because visceral fat isn’t just sitting there inside us. “Fat around the organs is definitely more risky than fat anywhere else in the body,” says Rozanne Kruger, associate professor in Dietetics and Human Nutrition at Massey University, who has led research into body composition.

“It’s been shown to increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, dyslipidaemia, glucose intolerance, inflammation and insulin resistance.”

Dr Kruger explains fat cells around the middle of the body produce inflammatory proteins that disrupt insulin regulation.

This increases the risk for type 2 diabetes. These inflammatory proteins also cause resistance to leptin – a hormone that regulates fat storage and how much energy we eat and burn.

How do I get it?

There is a genetic component; some of us are more prone to an ‘apple’ body shape. But normal weight obesity also develops over time. Diet and inactivity both contribute, even if they don’t cause weight gain.

Researchers looking at body composition say that younger, premenopausal women are particularly at risk of accumulating higher body fat, due to physical inactivity and unhealthy eating behaviours such as dieting and fast-food consumption.

Our bodies tend to change in composition over time, too: as we age, we lose muscle mass, especially if we’re not exercising those muscles. When we lose muscle, the proportion of fat in our bodies will naturally increase. Less muscle also means we’re inclined to gain more fat. It’s a bit of a vicious circle.

“Our metabolic rate drops as we age,” Dr Kruger says.

“The moment your metabolic rate starts to drop, and you eat the same as you always have, you are going to gain weight.”

Menopause is also a contributor for women, as hormonal changes mean fat is stored more centrally than before. This, coupled with a drop in the metabolic rate as we age, can cause weight gain and more central fat.

Stress also likely plays a role. The stress hormone cortisol has been found to be associated with higher levels of visceral fat, although researchers don’t understand fully what’s going on here. In any case, when we are stressed we tend not to eat as well and to exercise less; so that’s likely to have an effect.

How do I know if I have it?

A sure-fire way to know if you have normal-weight obesity is to be analysed for body composition. There are various methods for doing this, ranging from old-school callipers tests (notoriously unreliable) to what’s known as air displacement plethysmography (gold standard, but usually only available in research laboratories). More common is bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) – basically using body-fat recording tools – sometimes found in gyms and health clinics.

Short of being professionally analysed, there are some signs to look for and things you can measure yourself that might clue you in.

Check your shape

A good place to start is to assess your body shape. While we’re all genetically different, people who tend to gain fat around their chest and middle are likely to be more at risk of normal-weight obesity.

This is what we might call an ‘apple’ shape. If you’re more of a pear – who gains weight around the hips and thighs – you’re probably less likely to be harbouring visceral fat.

Measure your waist

Your waist measurement is an easy measurement to give you a quick check. Run a tape measure around your middle – note for men: this is not where your belt goes; rather it’s the point at the top of your hip bones, roughly where your belly button is. A waist measurement over 94cm for a man or 80cm for a woman could mean risky visceral fat lurks.

Figure out your waist-hip ratio

Dividing your waist measurement by the measurement of your hips is another indicator of visceral fat, and it works whatever your size.

Take the circumference of the widest part of your hips and bum. Divide your waist measurement by this number. For men, a ratio over 1 indicates higher risk and for women it’s over 0.85.

Test your strength

If you struggle to do a deep squat, a lunge or a push up, your muscle mass might be lower than is ideal.

Test yourself on some of these simple strength exercises; if your muscle mass is low, chances are your body fat is higher than is ideal.

Get your bloods done

Getting regular checks of your cholesterol and blood sugar levels, as well as getting your blood pressure checked, are all ways to check how healthy you are metabolically. Higher levels of these could indicate normal weight obesity.

Check your history

If a close relative – parent, brother or sister – has diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, or high cholesterol, you may be genetically predisposed to these conditions, too.

How can I reverse normal weight obesity?

Luckily, visceral fat is something we can reduce, and you may find it easier than shifting fat around hips and thighs.

“That’s often where people lose weight first”, Dr Kruger says. The solution is not just one thing, though. “It’s not just changing physical activity or changing diet; the answer is changing both. If you do that you have a bigger chance of reducing body fat”. Here are some tips:

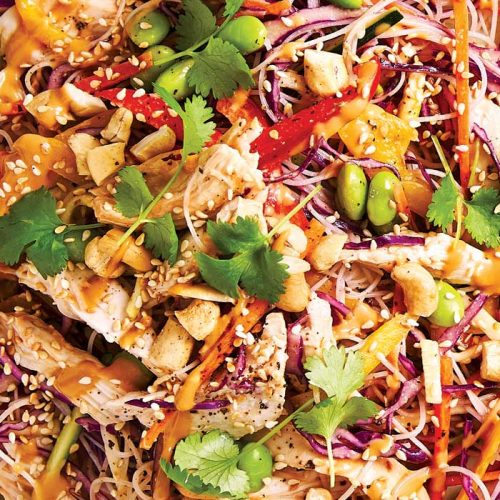

Tweak your diet

It’s easy to slip into eating habits we know might not serve us well. Getting back to a good, healthy diet full of unprocessed whole foods, tons of plants and not too much sugar, refined carbohydrate or saturated fat will help give you great fuel and energy.

Keeping an eye on portion sizes – and cutting them down if they’ve crept away from the half-plate-of-veges model – will help, too. And so will cutting down on alcohol. If you’re a sugary drink lover, cutting back is a good idea; higher intakes of sweet drinks have been associated with higher levels of visceral fat.

Move your body

Getting exercise is crucial to burn visceral fat. Any movement is good – walking, running, swimming – just get moving and keep it up regularly.

Get into strength training

Building muscle is a great way to reduce body fat, and a powerful way to reduce visceral fat in particular. Not because fat turns into muscle, but because the more muscle you have, the more energy you’ll burn, even when you’re not exercising. And that will help gradually reduce your body’s fat stores. Being strong is also great for our bones, especially as we age.

Article sources and references

- Davis SR. as the Writing Group of the International Menopause Society for World Menopause Day. 2012. Understanding weight gain at menopause. Climacteric 15:419-29https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22978257

- Gearon E. 2017. BMI is underestimating obesity in Australia, waist circumference needs to be measured too, theconversation.comhttps://theconversation.com/bmi-is-underestimating-obesity-in-australia-waist-circumference-needs-to-be-measured-too-89156

- Gearon E et al. 2018. Changes in waist circumference independent of weight: Implications for population level monitoring of obesity. Preventative Medicine 111:378-83https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29199118

- Kruger R et al. 2015. Predictors and risks of body fat profiles in young New Zealand European, Māori and Pacific women: study protocol for the women’s EXPLORE study. SpringerPlus 4:128https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4372618/

- Lasikiewicz N et al. 2013. Stress, cortisol and central obesity in middle aged adults. Obesity Facts 6: S44https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/28068/

- Ma J et al. 2014. Sugarsweetened beverage consumption is associated with abdominal fat partitioning in healthy adults. Journal of Nutrition 144:1283-90https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24944282

- Oliveros E et al. 2014. The concept of normal weight obesity. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases 56:426-33https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S003306201300176X?via%3Dihub

- University of Michigan News. Hefty people can have healthy hearts, news.umich.edu Accessed April 2019https://news.umich.edu/hefty-people-can-have-healthy-hearts/

- Wang B et al. 2015. Prevalence of metabolically healthy obese and metabolically obese but normal weight in adults worldwide: A meta-analysis. Hormone and Metabolic Research 47:839-45https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26340705

www.healthyfood.com