Most of us aren’t aware of how much effect sleep, mealtimes and the day/night schedule have on our health. HFG uncovers it all.

We live in a 24-hour culture. We have food accessible whenever we want. Some shops are open 24 hours a day. We work shifts. We watch TV into the early hours.

We have never been so much in control of what we do and when. But one aspect we have no control over is how our bodies are reacting to these changes — and they’re not reacting well.

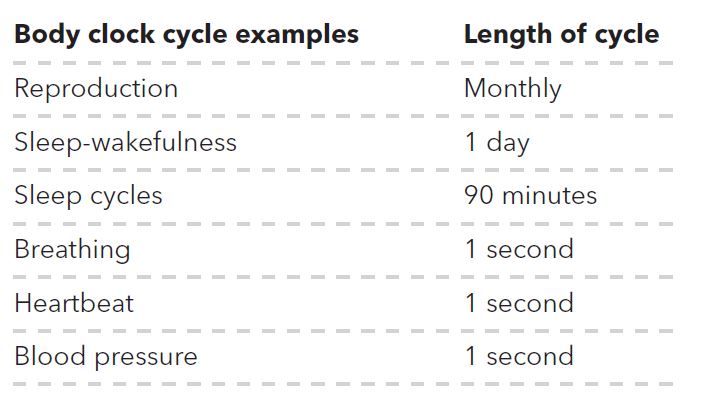

Our bodies are governed by a series of biological clocks, working together or interlinking at certain times in their cycles. These cycles are responsible for allowing our bodies to perform set tasks designed to keep us healthy. If one clock isn’t on time it sets other clocks back. The result is the rhythms no longer synchronise and our health may start to fail. Our 24-hour culture is changing our natural rhythms.

Different biological rhythms

Circadian rhythms are daily patterns in biochemical, physiological and metabolic processes, such as sleeping and waking, body temperature, hormone secretion patterns, blood pressure, alertness levels and reaction times, that occur over a 24-hour period.

Diurnal rhythms are circadian rhythms that are synchronised with the day/night cycle and are affected by environmental cues such as light and dark.

Ultradian rhythms are biological rhythms that happen recurrently, in less than 24 hours. Examples are our heartbeat, appetite and sleep stages.

Infradian rhythms last longer than 24 hours and can be weekly, monthly or yearly. The female menstrual cycle is a good example of a monthly infradian rhythm.

What controls the rhythms in our body?

A centre called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) found in our brain is the main site controlling the timing of our body clocks. Other less influential clocks are found in our heart, lungs, liver, intestines, adrenal glands and fat tissue.

The main trigger that resets our SCN is the light/dark cycle. However, a secondary trigger takes over when food intake is restricted. The timing of meals becomes the primary trigger that resets our SCN clock, but, when food is plentiful, the reset trigger reverts to the light/dark cycle.

Other rhythms in our body are triggered by eating times, social contact, exercise, genes and hormones, to name a few.

What happens when our body clocks keep the wrong time?

Disruption to the time that our body clocks keep (circadian disruption) can cause our body to not perform as it should. Animal and human research has implicated circadian disruption in:

- Reduced life expectancy

- Increased risk of and progression of certain types of cancer (breast, endometrial, prostate, colorectal, melanoma)

- Increased risk of cardiovascular disease (stroke and heart attack)

- Obesity and metabolic syndrome

- Mood disorders (seasonal affective disorders, major depression, sleep disturbances)

- Cognitive impairment (dementia, Parkinson’s disease).

Sleep

The one rhythm to rule them all

Over the past century, the amount of sleep we get, on average, every night has reduced by about 1½ hours. Most adults need about 6-8 hours’ sleep each night, which is broken into 90-minute sleep cycles. We work night shifts, work and live in environments with artificial lighting and watch TV or use electronic devices at night. All of these affect our sleep cycles. And it’s not just sleep deprivation that leaves us tired and grumpy — the effect of the changes in our sleep patterns shows in our health by shifting the timing of our body clocks.

The shift in light/dark cycles is a major environmental cue that resets or triggers our daily body clocks. light causes reactions in the body that affect the immune system and production of melatonin (a key hormone needed for sleep), increase the heart rate and release adrenalin and other hormones we need to wake up.

The amount of natural light we’re exposed to during the day has an impact on our sleep cycles. Less time in natural light results in poorer sleep quality. Although it may seem like the light in our offices or homes is bright, artificial lights only give one per cent of the brightness we experience with natural light. This lower level of light is not as effective at triggering the SCN in our brain to reset our circadian rhythms.

Blue light coming from computer screens, tablets and smartphones changes body rhythms associated with increases in heart rate, core body temperature and alertness. Even low-lit computer screens have this effect. These responses prevent our body triggering sleep circadian rhythms, shifting our sleep cycles later into the night. Using bright lights has been a strategy for shift workers to overcome periods of fatigue, but this can also negatively affect sleep quality.

Having a disrupted sleep cycle can affect other areas of our health.

In people with cancer, research has shown that changes to the cycles of our natural body clocks can affect sleep cycles. One study found that sleep cycles were disturbed, depending on the severity of the cancer. Those with single-site tumours that were surgically removed were least sleep affected, and those with metastatic cancer had their heart rate more affected by circadian changes.

In those with cachexia (weight loss associated with a tumour), night-time heart-rate cycles were disrupted, failed to drop (as they would normally) and remained high, possibly contributing to weight loss caused by increases in metabolic rate.

Sleep cycle changes

Also increase risk of unintentional weight gain

Circadian disruptions can affect metabolic activities such as how our body processes and stores fat and carbohydrate. As we stay up later, eat later or eat during the night we shift the natural rhythms that help our body effectively metabolise, use and store the nutrients we eat.

Research looking at the health effects of shift work has shown that working nights increases the risk of obesity, cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. One of the causes is thought to be changes in the body clocks that control melatonin which plays a role in glucose metabolism. If melatonin levels are low (as they are in night-shift workers) then there is a decrease in insulin sensitivity and an increase in fat storage — both being precursors to obesity, cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.

Nutrition and body-clock cycles

Glucose, fats, proteins and nutrient-sensing molecules, can change the timing of our body clocks and the size of the effect of these rhythms. And it’s not just what we eat but when we eat that can also make changes. Eating at the ‘wrong’ time of day (or night) increases the risk of obesity, insulin resistance, increased fat storage and inflammation. Not having a fasting period between meals (snacking or grazing) also dampens down the effect of our body clocks.

A recent study with 156 adults used a mobile app to monitor eating habits. Results showed that eating occurred almost continuously throughout the day.

The typical three-meal-a-day patterns weren’t seen in most individuals and the number of eating events per day ranged from three to 10. Only 25 per cent of meals occurred After more than six hours fasting. Less than 25 per cent of total energy was eaten before noon, and over 50 per cent after 6pm.

Night eating syndrome, an eating disorder that involves eating more than 25 per cent of energy intake after dinner or during the night at least twice a week, is linked to weight gain, especially in those aged 31-60 years old. Eating later at night and waking during the night to eat both reduce sleep time, which affects our body clocks. And hormonal clock delays have been found, which may impact on weight, blood pressure and blood fats.

Food intake plays an important role in keeping our body clocks ticking on time. Food restriction can change the genes that control some of the body rhythms but it’s not clear whether this has a direct impact on weight gain.

A change in mealtimes could also affect our weight. leptin is a hormone that reduces hunger and increases energy usage. Leptin is controlled by body rhythms that are triggered by protein intake. A high energy intake, constant snacking and change in mealtimes could all affect our leptin cycles, meaning we don’t feel full and our energy usage isn’t increased.

Circadian disruption (when our body clocks are out of their correct rhythm) is more common in people with central obesity (apple shape) than those who carry weight around the hips.

Central obesity is a risk factor for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Body clock rhythms and metabolism

How our body uses and stores carbohydrates and fats is regulated by our body clocks. In healthy people the morning is when everything works most efficiently. The liver functions well to metabolise fats and peripheral sensitivity to insulin and blood sugar control is top notch. But, as the day goes on, things start to slide. Those with normal blood sugar control may even register within pre-diabetic blood sugar levels by the evening because insulin sensitivity (how efficiently the body uses insulin to lower blood glucose levels) declines.

But it’s back to full working order again by breakfast. Insulin secretion is highest at lunch time and lowest during the night (when no food is expected to be eaten). Insulin sensitivity declines after the body releases cortisol as part of the wake-up plan. However, in those with type 2 diabetes insulin sensitivity is lowest overnight and morning and improves during the day.

Metabolic rates are also, generally, highest in the morning because of thermogenesis, the body producing heat from food.

Although the mechanism is not yet understood, several studies have found thermogenesis is significantly higher in the morning than in the evening.

However, we don’t really know whether this rhythm for thermogenesis is altered for shift workers operating on a different 24-hour pattern.

How do circadian rhythms affect mood?

Changes in sleep, energy and appetite are often reported alongside changes in mood. But it is still unclear whether these disturbances are part of the cause of mood disorders or an effect of mood disorders.

Genes that regulate our body clocks have also been implicated in mood regulation, major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder. Neurotransmitters can affect our sleep patterns and are released in their own rhythm.

Lack of sleep or too much sleep is included in the diagnostic criteria for several psychiatric disorders. Regardless of whether sleep cycle disruption is a cause or effect of mood disorders, sleep disruption has been shown to have negative health outcomes such as increases in obesity and high blood pressure.

Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) is a type of depression where symptoms come on as the seasons change, usually to autumn or winter, because of the shorter days. SAD is thought to be linked with lower sunlight levels affecting melatonin levels and disrupting circadian rhythms. Lower light levels may make the body produce more melatonin, making a person sleepy. And, while there’s more melatonin being produced, a lack of sunlight is also thought to lead to lower levels of the ‘happy hormone’, serotonin.

One of the treatments of SAD is light therapy, which helps bring light/day responses back to normal. The bright light that is used for people who work shifts to keep them alert can also improve mood and sleep cycles in SAD.

Can my body clocks tell me when it’s best for me to exercise?

Whether you’re an athlete in training or just out for a daily walk, there are rhythms that tell us when the best time is to exercise.

Studies have shown peak performance is linked to higher core body temperature because of increased cognitive performance, energy metabolism, improved muscle compliance and strength. Steroid hormones, such as cortisol and testosterone, that affect performance also have links to the rhythms of our body clocks.

Testosterone promotes muscle building. Our internal body clocks make testosterone levels higher in the morning and decrease during the day. However, higher cortisol levels have been linked with lower performance and cortisol also peaks in the morning and drops during the day.

Our body clocks also influence what nutrition our body needs to refuel during exercise. An increase in core temperature may lead to an increase in carb use over fat as a fuel source.

So exercise in early evening, when our core temperature is higher, burns more glucose than fat. It seems that the best time to exercise may be early evening, not the early morning that many people choose. A study found spending an extra 20 minutes warming up in the morning increased body temperature to that of early evening. So, if you’re training for strength and stamina you may need to schedule more warm-up time, if exercising in the morning.

Research looking at exercise timing for people with type 2 diabetes shows the benefit of exercise after meals rather than before, and especially after the evening meal.

Increases in blood sugar and fat levels are lessened if exercise is taken after a meal and the biggest benefit is seen when exercise is enjoyed after the evening meal.

Healthy by clockwork

Schedule your day to keep your body clock on your side

Get regular, uninterrupted sleep

Sleep is fundamental to making sure all our body clocks are working with us.

- Get plenty of natural daylight in the morning after you’ve woken up

- Use low-level artificial lighting in the evening

- Turn all lights off at sleep time, including night lights

- Don’t use computers or electronic devices at least one hour before bedtime

- Talk to your doctor about a short course of melatonin to re-programme your sleep cycle, if you’ve had ongoing disturbed sleep routines.

Eat regular meals and cut the snacks

Your body needs to have some time between meals with no food intake. Snacking is a modern trend with no physiological rationale. And yes, your trim flat white mid-morning is considered a snack. It’s hard to adjust to not having snacks, but your body clock will thank you for it.

- Aim for three meals each day of equal energy amounts

- Try cutting out one snack a day, every day for a month

- Use distraction when you feel like snacking – go for a walk, stretch, have a drink of water.

Exercise in the early evening

Exercising in the early evening is best if you’re training or just going out for a gentle walk. If exercising in the morning is the only time you can fit it in, maximise the benefits by doing an extra 20 minutes warm up to increase your core temperature.

What foods to eat when?

Timing what foods you choose to eat according to how your body can best process and store them gives you extra health benefits and makes weight, blood sugar and cholesterol management easier.

Breakfast

Your insulin is working well. Eat some wholegrain or high-fibre carbohydrates to keep you full for longer. Your body also processes fat more efficiently in the morning, so add some healthy fat to breakfast, such as avocado on wholegrain toast.

Lunch

Lunch is the most forgiving meal. Eating between 12 midday and 2pm is where less healthy choices will have fewer repercussions on your body. Make sure you have a filling lunch with high-fibre vegetables, whole grains, protein and healthy fats to see you through until dinner.

Dinner

Your insulin is less effective now. Focus on filling your plate with vegetables and protein with only a small amount of wholegrain or high-fibre carbohydrates. If you’re following a low-carb diet, then following it for dinner is more important to your body than following it in the morning.

Article sources and references

- Allison KC & Goel N. 2018. Timing of eating in adults across the weight spectrum: Metabolic factors and potential circadian mechanisms. Physiology & Behaviour 192, 158-66https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29486170

- Cornelissen G & Otsuka K. 2017. Chronobiology of aging: A mini-review. Gerontology 63:118-28https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27771728

- Garaulet M et al. 2010. The chronobiology, etiology and pathophysiology of obesity. International Journal of Obesity 34:1667-83https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20567242

- Gill S & Panda S .2015. A smartphone app reveals erratic diurnal eating patterns in humans that can be modulated for health benefits. Cell Metabolism 22:789-98https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26411343

- Grainger R. 2019. Seasonal Affective Disorder, healthnavigator.org.nz Accessed August 2019https://www.healthnavigator.org.nz/health-a-z/s/seasonal-affective-disorder/

- Heden TD & Kanaley JA. 2019. Syncing exercise with meals and circadian clocks. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews 47:22-8https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30334851

- Johnston JD. 2014. Physiological links between circadian rhythms, metabolism and nutrition. Experimental Physiology 99:1133-7https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25210113

- Moser M et al. 2006. Why life oscillates - from a topographical towards a functional chronobiology. Cancer Causes & Control 17:591-9\https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16596315

- Münch M & Bromundt V. 2012. Light and chronobiology: Implications for health and disease. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience14:448-53https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3553574/

- Ruddick-Collins LC et al. The Big breakfast study: Chrono-nutrition influence on energy expenditure and bodyweight. Nutrition Bulletin 43:174–183https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29861661

- Sparks J. Biopsychology: Infradian and Ultradian Rhythms Explained, youtube.com/ watch?v=knSNZACAe6Y Accessed August 2019https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=knSNZACAe6Y

- Teo W et al. 2011. Circadian rhythms in exercise performance: Implications for hormonal and muscular adaptation. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine 10:600-6https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3761508/

- Wirz-Justice A. 2003. Chronobiology and mood disorders. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 5:315-25https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22033593

- Zaki NF et al. 2018. Chronobiological theories of mood disorder. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 268:107-18https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28894915

www.healthyfood.com