Mental health dietitian Brad Brosnan explores the complexities of the eating disorder, bulimia nervosa.

Sam*, a university student and marathon runner, always pushed himself to be the best. His physique and food choices were no exception. To ensure optimum performance in both athletics and life, Sam focused on being ‘healthy’, ‘clean eating’ and staying slim. His friends supported his training and diet choices so, when Sam decided to eat a piece of cake, a well-meaning pal discouraged it. Sam quickly got ‘back on track’ and soon added tougher diet restrictions that went far beyond ‘clean eating’. Eventually, his intense marathon training was accompanied by a strict intake of only oats with water and salad. Sam vowed not to touch what he viewed as ‘bad’ food again, until he won the race.

Then Sam won but didn’t feel satisfied. The scales had tipped, not only for the race but also in his life. Sam’s relationship with food shifted. He felt he had to restrict to maintain the body he expected. But his eating began swinging from restrictive to excessive. The moment he touched a carby noodle dish while out for dinner with friends, he suddenly wanted to eat everything on the table. A cycle of binge eating began and, within days, he was gorging himself on chocolate, biscuits and cereal. When deep regret set in after each secret session, Sam was desperate to get the ‘bad’ food out of his body, so made himself throw up. A cycle of bingeing and purging began.

Bulimia nervosa can begin after a person diets or restricts their food intake. But this condition is about much more than just food. Bulimia is a serious mental health condition, heavily related to self-image, preoccupation with weight and body shape and self-judgment of perceived flaws. It is a potentially life-threatening eating disorder but is treatable. In Sam’s case, dieting and strict eating weren’t just about the marathon.

Constant thoughts about an ‘ideal’ body shape and weight made him feel he would never be good enough.

What causes bulimia?

There is no single cause of bulimia, but the following can be risk factors or triggers:

- Low self-esteem or poor body image

- High personal expectations

- Trouble with drugs or alcohol

- Depression or anxiety and poor coping strategies

- Social and family encouragement to lose weight

- Experiencing stigma or bullying about weight

- Extreme dieting for ‘bulking’ and body sculpting/building

- Sports that require athletes to be thin, eg, dancers, jockeys and gymnasts

- Previous trauma

- Growth spurts

- Diabetes

- Being in a larger body

- Accidental weight loss as a result of illness

- Maintaining a body weight lower than natural

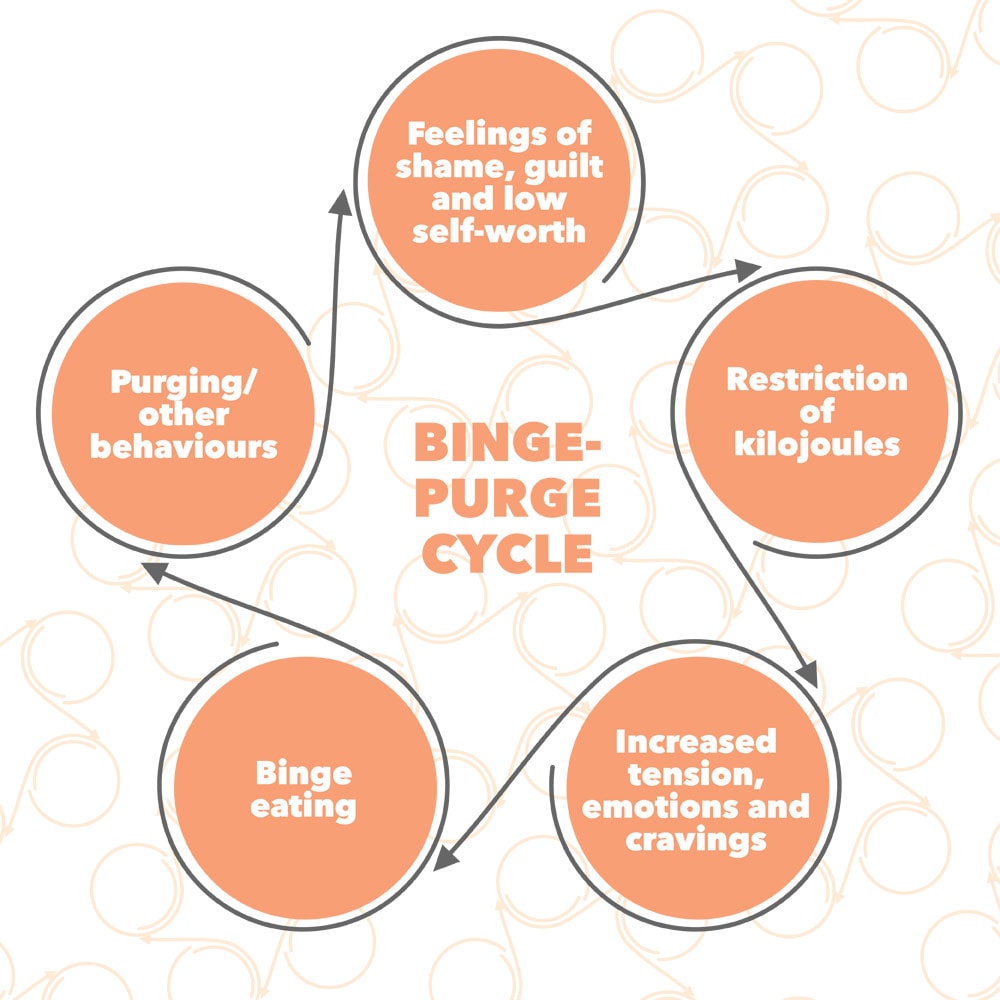

Binge-purge: a cycle of emotions

According to eating disorders dietitian Sylvia Pyatt, people with bulimia can feel out of control and unable to stop eating during a binge. Often, they will develop strict food rules, labelling food as ‘good’ and ‘bad’. These rules elicit guilt and shame during a binge when they consume large volumes of ‘forbidden’ food. This loss of control is also associated with the powerful and overwhelming fear of gaining weight. Despite this fear, it is often energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods people with bulimia turn to to make themselves feel better.

Senior clinical psychologist Eve Hermansson-Webb explains high-carb foods provide the body with the most accessible energy, which becomes necessary after periods of deprivation. Such foods can also feel good to eat. After bingeing, people often experience a panic response, which can lead to compensatory behaviour, such as purging.

Sometimes, Sam would sneak out at night for ‘junk’ food, or even steal food from his flatmates. His binges would often end only if he was interrupted, fell asleep or because his stomach hurt so much from being over-full. He would then feel regret and purge. Dr Hermansson- Webb says most people with bulimia “judge their self-worth largely in terms of their weight and shape, and their ability to control these things”.

Sam’s bingeing and purging may have provided him with short-term freedom from internal struggles and uncomfortable feelings, but bulimia wasn’t about food; it was about him trying to gain self-control through strict and unrealistic rules around eating, weight and shape, and exercise.

Myths about bulimia:

- You have to purge to have bulimia

Other bulimic behaviours include laxative abuse, restricting and excessive exercise. - Only young women have bulimia

More women than men are diagnosed but bulimia doesn’t discriminate by age, sex or race. - Men don’t feel body image pressure

Men also struggle with self-image and body weight. - If I could just lose weight or follow my diet, I wouldn’t have bulimia

The opposite is true, bulimia is sustained by over-strict dieting and pursuit of weight loss or a body shape that is not genetically natural to that person. - Bulimia is caused by unrealistic images in the media

While sociocultural factors, such as idealised body images, can contribute to bulimia, the causes are many and include biological, social and environmental contributors.

Although the American Psychiatric Association defines bulimia as recurrent episodes of regular binge eating with compensatory behaviour to prevent weight gain, bulimia isn’t exclusive to purging. Other compensatory behaviours can include abusing laxatives and other medications, enemas, restricting kilojoules, excessive exercise, or avoiding certain foods between binges.

Having bulimia raises the risk of significant medical complications, anxiety and depression, social and relationship problems and suicidal thoughts and behaviours. It’s estimated that about 2 per cent of women and 0.5 per cent of men will experience bulimia during their life with most cases beginning in the late teens and early 20s. Bulimia nervosa can occur in any body weight.

Despite multiple risk factors, it’s puzzling that someone who is able to maintain a healthy body weight, or an elite athlete like Sam, is vulnerable to binge-purge cycling. Dr Hermansson-Webb says individuals who diet or restrict their eating, even in subtle ways, can set themselves up for binge eating. And it makes sense that starvation or the threat of future starvation may trigger people to binge eat. Dr Hermansson-Webb explains despite attempts to restrict food or diet, our bodies are programmed to get back to a genetic set point weight.

So, when people overvalue weight or shape and insist upon a desired weight that is lower than natural for them, it can lead to the suppression of healthy body weight. This suppression, in turn, can lead to eating disorders such as bulimia.

Complications

While some people with bulimia will become underweight, many maintain a weight within the ‘healthy’ range. But self-induced vomiting is itself damaging to the body and carries significant health risks. Bulimia may also cause numerous other serious complications including:

- Self-injury, suicidal thoughts, or suicide

- Dehydration

- Kidney failure

- Heart problems

- Lung damage

- Severe tooth decay and gum disease

- Absent or irregular menstrual periods

- Digestive problems

- Poor self-esteem and problems with relationships and social functioning

- Anxiety and depression

- Alcohol or drug abuse

- Sudden death

Anyone experiencing symptoms of bulimia should seek help from their GP as quickly as possible, even if bingeing or purging is occasional. Dr Hermansson-Webb says a good doctor will ask questions to assess the nature of symptoms, arrange any necessary tests to monitor physical health, and can make a referral to a mental health service for a more specialised assessment.

How is bulimia treated?

Bulimia is diagnosed based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition criteria. It is treated by a mental health therapist, usually a clinical psychologist, psychiatrist or psychotherapist. Treatment may involve input from a dietitian but the first lines of treatment for bulimia are psychological therapy.

The most effective form of therapy has been shown to be cognitive behavioural therapy. This type of treatment focuses on recognising and overcoming the underlying binge-purge triggers, exploring feelings and causes, and providing the support necessary to return to regular eating behaviours for that individual.

Another form of therapy is family-based treatment, which is often used in treating adolescents and involves parents taking an active role in their child’s recovery.

“The treatment should involve encouraging the client to stop pursuing weight loss, to start practising regular eating (including eating foods they enjoy) and help with learning to accept their body weight and shape for where it sits naturally, and not trying to change it,” Ms Pyatt says. Depending on the patient, medication, such as antidepressants, can be used in addition to therapy. With proper treatment, most people with bulimia can recover, but it takes time, so it’s important to establish an ongoing relationship with a trusted health professional.

Signs a person may be suffering with bulimia:

- Frequent weight fluctuations

- ‘Body checking’, excessive weighing, ‘looking for fat’, seeking validation about weight and size

- Obsessive food behaviours including weighing food, counting kilojoules, recording intake

- Strong beliefs around food being ‘bad’ or ‘good’

- Hidden food or food wrappers

- Avoiding eating in front of others

- Food going missing

- Extreme anxiety around eating certain foods

- Finding vomit in the toilet

- Purchasing and storing laxatives

- Excessive time spent exercising

- Long periods of time without food – feeling dizzy or faint from restriction of food

- Poor blood results for those prescribed medication (eg, suddenly high blood sugar levels in patients prescribed insulin for type 1 diabetes).

Advice for talking to a loved one with bulimia:

- Avoid talking about kilojoules, ‘good’ and ‘bad’ foods, and weight

- Show them you value things about their personality or talents rather than discussing weight and shape. This applies to all bodies, including your own

- Express concern non-judgementally. Let them know you are happy to listen, or suggest they talk to someone they are comfortable with.

Luckily, Sam sought treatment when he became aware he had a problem. He realised he needed to rewire his brain, to challenge his “all or nothing thinking” and how he viewed himself and others. Sam continues to work on his relationship with his body.

Instead of eating to control emotions, he eats to nourish his body. Most importantly, how he values himself has changed. The process took a long time and is a daily choice he still makes, but these changes will serve him the best in life. Sam is in it now for the long run.

*Not his real name

Eating disorder support

NZ: edanz

Australia: Eating Disorder Hope

UK: Beat Eating Disorders

US: ANAD

For more on eating disorders you might be interested in: Gaps in eating disorder understanding, 9 ways to support someone with an eating disorder at Christmas, Too healthy for your own good or How to help when eating is scary

Article sources and references

- Alvarenga MS et al. 2003. Nutritional aspects of eating episodes followed by vomiting in Brazilian patients with bulimia nervosa. Eating and Weight Disorders 8:150-6https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12880193

- American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington DChttps://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm

- American Psychological Association. 2017. What Are Eating Disorders?, psychiatry.orghttps://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/eating-disorders/what-are-eating-disorders

- Hail L & Le Grange D. 2018. Bulimia nervosa in adolescents: Prevalence and treatment challenges. Adolescent health, medicine and therapeutics 9:11-6

- Hay P et al. 2014. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of eating disorders. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 48:1-62https://www.ranzcp.org/files/resources/college_statements/clinician/cpg/eating-disorders-cpg.aspx

- Kalm LM, Semba RD. 2005. They starved so that others be better fed: Remembering Ancel Keys and the Minnesota experiment. The Journal of Nutrition 135:1347-52https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15930436

- Kaye WH. 1993. Amount of calories retained after binge eating and vomiting. The AmericanJjournal of Psychiatry 150:969-71https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8494080

- Mehler PS & Rylander M. 2015. Bulimia nervosa - medical complications. Journal of Eating Disorders 3:12https://jeatdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40337-015-0044-4

- Rienecke RD. 2017. Family-based treatment of eating disorders in adolescents: current insights. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics 8:69-79https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25685349

www.healthyfood.com